The central aim of the 2020 UTS Design Futuring Report is to imagine and visualise alternate worlds in the absence of the conceptual impediment of technology conceived as selective novelty. The theoretical cornerstone of our approach is David Edgerton’s The Shock of the Old (2008). Edgerton makes a wide-ranging and in-depth argument that challenges approaches to histories of technology that focus too much on innovation as opposed to use:

By thinking about the history of technology-in-use a radically different picture of technology, and indeed of invention and innovation, becomes possible. A whole invisible world of technologies appears. It leads to a rethinking of our notion of technological time, mapped as it is on innovation-based timelines. Even more importantly it alters our picture of which have been the most important technologies. It yields a global history, whereas an innovation-centred one, for all its claims to universality, is based on a very few places. It will give us a history which does not fit the usual schemes of modernity, one which refutes some important assumptions of innovation-centric accounts. (2008, xi)

Thinking of technology as innovation misconstrues understandings of the relative impact of different technologies over time. Edgerton cites the example of steam power among many others, which “was not was only absolutely but relatively more important in 1900 than in 1800” (2008, xi). Likewise, the sewing machine tells a story about technological change that is far more “jumbled up” and irregular than understandings of technological diffusion that follow a linear pattern of increasing and decreasing adoption. While sewing machines might not come to mind as a particularly conspicuous household technology in America or Britain in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, in rural China, Andean Peru and northern Thailand, for example, they remain important personal belongings (2008, 58-59). Edgerton offers an impressionistic though compelling insight into the polytemporal rhythms of technological change in the following two scenarios involving the sewing machine:

In Mae Hong Son, northern Thailand, in April 2002, treadle-operated Singers decorated with a sticker celebrating 150 years of Singer machines were on sale alongside white goods, next to an internet café. At the other end of the world, an expensive (male) tailor working alone making men’s suits in Lecce, Italy, also used a treadle operated Singer. (2008, 59)

Most technologies are more richly understood by taking a longer view of history and a broader view of culture than innovation-centric accounts tend to invite. Edgerton argues histories, and by extension futures, of technological change should place as much emphasis on what he describes as ‘creolisation’ as origin stories and much emphasis on failure, devaluation, ambiguity, ambivalence and reconfiguration as fast growth, widespread impact and coherence.

Thinking of technology as innovation also excludes our many and varied relationships with things. The “whole invisible world of technologies” mentioned by Edgerton tends to remain in the background when popular, unexamined definitions of technology are used in the envisioning of alternate worlds, which tend stereotypically to be populated by technological agents performing various labour saving miracles or advancing comfort-and-convenience-oriented visions of leisure.The tight association between technology and industrial progress is relatively recent. As Schatzberg (2006) and others (Oldenziel 1999; Marx 1994; Kline 1995) have shown, in nineteenth century English, ‘technology’ was a relatively specialised term that named "field of study concerned with the practical arts” (2006, 487). It was only in the early twentieth century that technology came to be more exclusively associated with the products of industry, applied science and associated with the progress of civilisation (Schatzberg 2006).

Definitions should be expected to change in such ways based on the dynamics of usage over time. Looking to the past can, however, be a thought-provoking reminder when present usage limits the scope and force of our interpretative efforts. As the opening quotation from Edgerton suggests, this is certainly the case when the contemporary, popular definition of technology is used as a springboard to imagine different futures.The lack of originality described by Edgerton is nowhere more explicit than in industry reports that attempt to bring to life forecasted technological trends through the use of scenario visualisations. These visualisations, often in the form of 12-24 frame storyboards, depict the so called everyday life of people in future contexts where emerging technologies from the present have undergone anticipated rapid growth, become more impactful and more coherent (see for example, Deloitte Water Tight 2.0, pp. 12-14).

To some extent, the limitations of such scenario visualisation are written into the institutional arrangements that lead to their creation. In other words, the visualisations are part of reports the very purpose of which is to focus on new technologies, defined as selective novelty, not on socio-technological change or everyday practices as complexly and subtly conceived. Nonetheless, as a recent desk-based review of 64 digital technology and energy industry reports from the Monash University Emerging Technologies lab has demonstrated (Dahlgren et al 2020), the exploration of human-technology relations in such reports barely lives up to the name ‘exploration’ on account of derivative and conservative visions they promote. As the Monash team point out, there is a tightening feedback loop between such scenario work and the kinds of futures for which we prepare and which we invest in creating. The words ‘future’ ‘technology’ and ‘scenario’ when paired together seem in this sense to have a paralysing, algorithmic effect on the very imaginative faculties that are meant to play a key role in helping us travel from the supposedly constrained horizons of the present to more airy, malleable future realms.There is a rich, recent history of approaches to futuring in the university sector that have attempted to address the lack of originality in futures thinking. The influential work of Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby at the Royal College of Arts, Julian Bleecker’s Near Future Laboratory, the Social Futures Laboratory at Lancaster University, Alex Coles’ work at University of Huddersfield, Stuart Candy and Jake Dunagan’s work at Carnegie Mellon University, and many other futures-oriented education and research programs, all use ‘the future’ as a design context to provoke distinctively speculative approaches to imagine different possibilities for socio-technical change. The work of the 2020 UTS Design Futuring Report follows in this tradition, though inevitably our different theoretical precedents, pedagogical emphasises and regional concerns have led to work that exhibits sometimes-subtly-sometimes-markedly different interpretive affordances and a different look and feel. Encapsulating the nature of these local variations, without resorting to dogma, is in part the aim of this report.

The set of focuses listed below emerged as key learning objectives in the unlearning-learning process characteristic of obtaining and applying genuine new knowledge. While these focuses might be shared to varying degrees across the many different design futuring efforts listed above, grouped together they capture what makes the work evidenced in this report distinctive from theoretical and practical perspectives.

Continue ︎︎︎

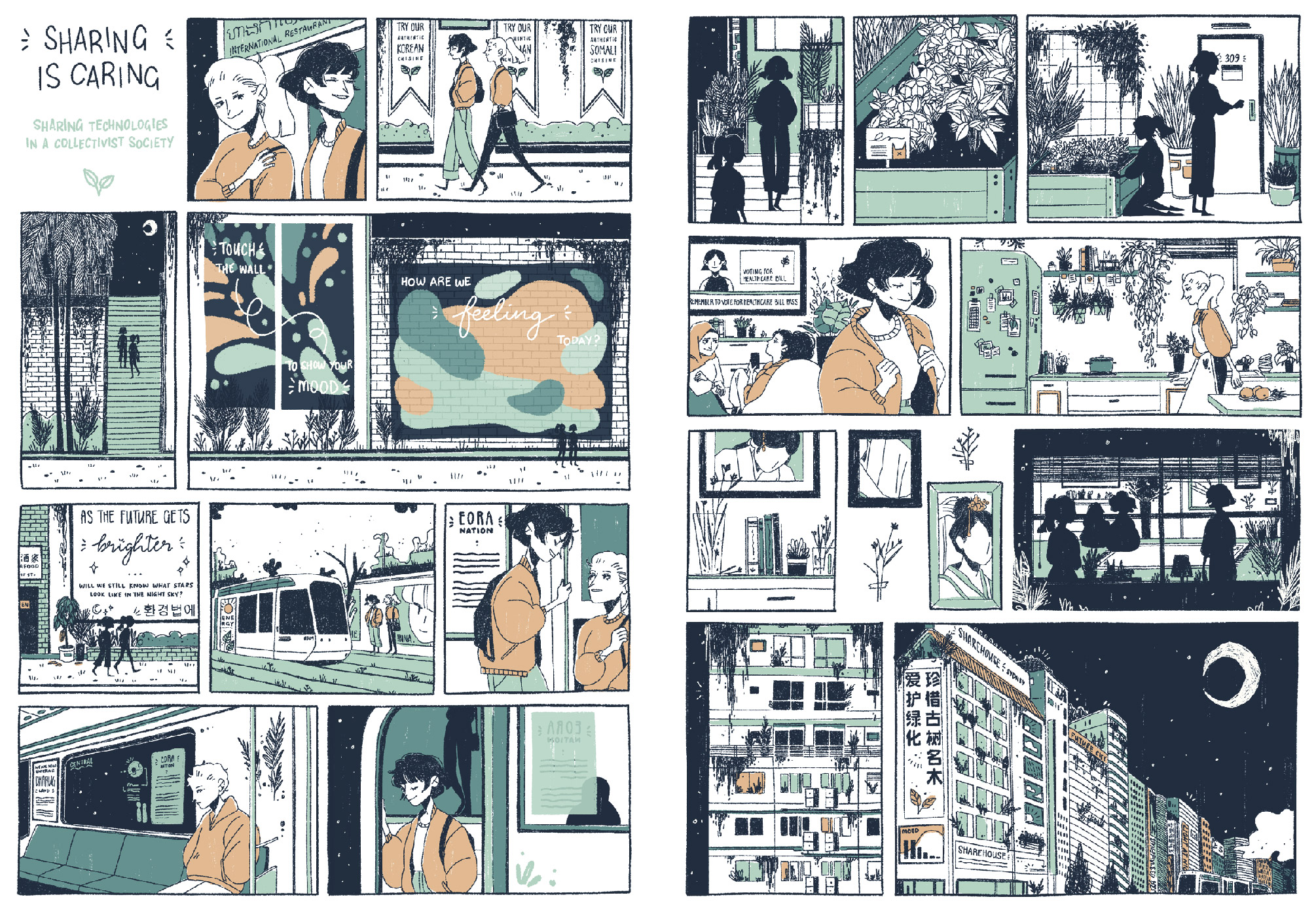

[04] Sharing is Caring: sharing technologies in a collectivist society

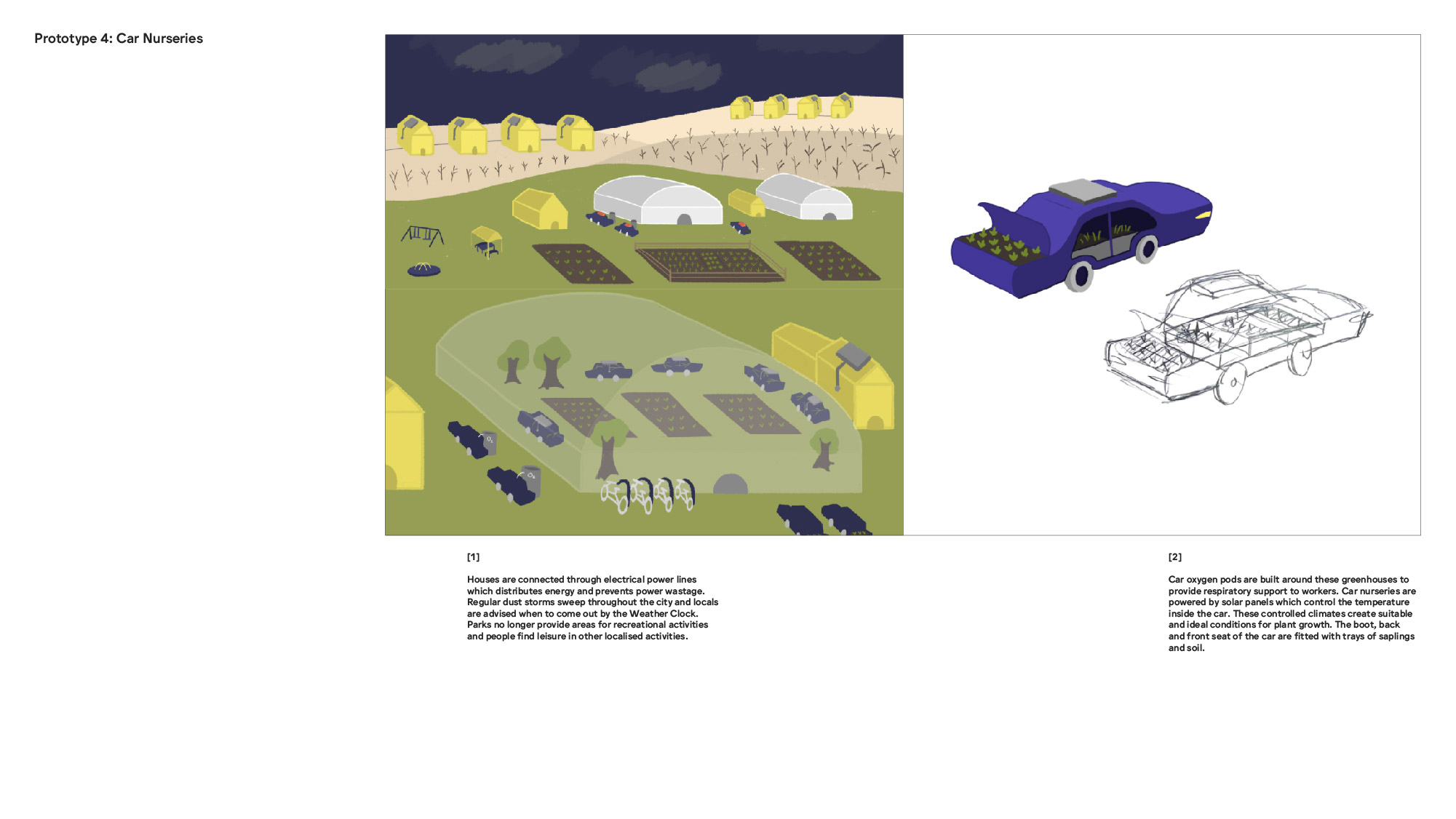

[05] Green Exertion

[06] Future Cultures: use-based technology as a system to reclaim control and agency

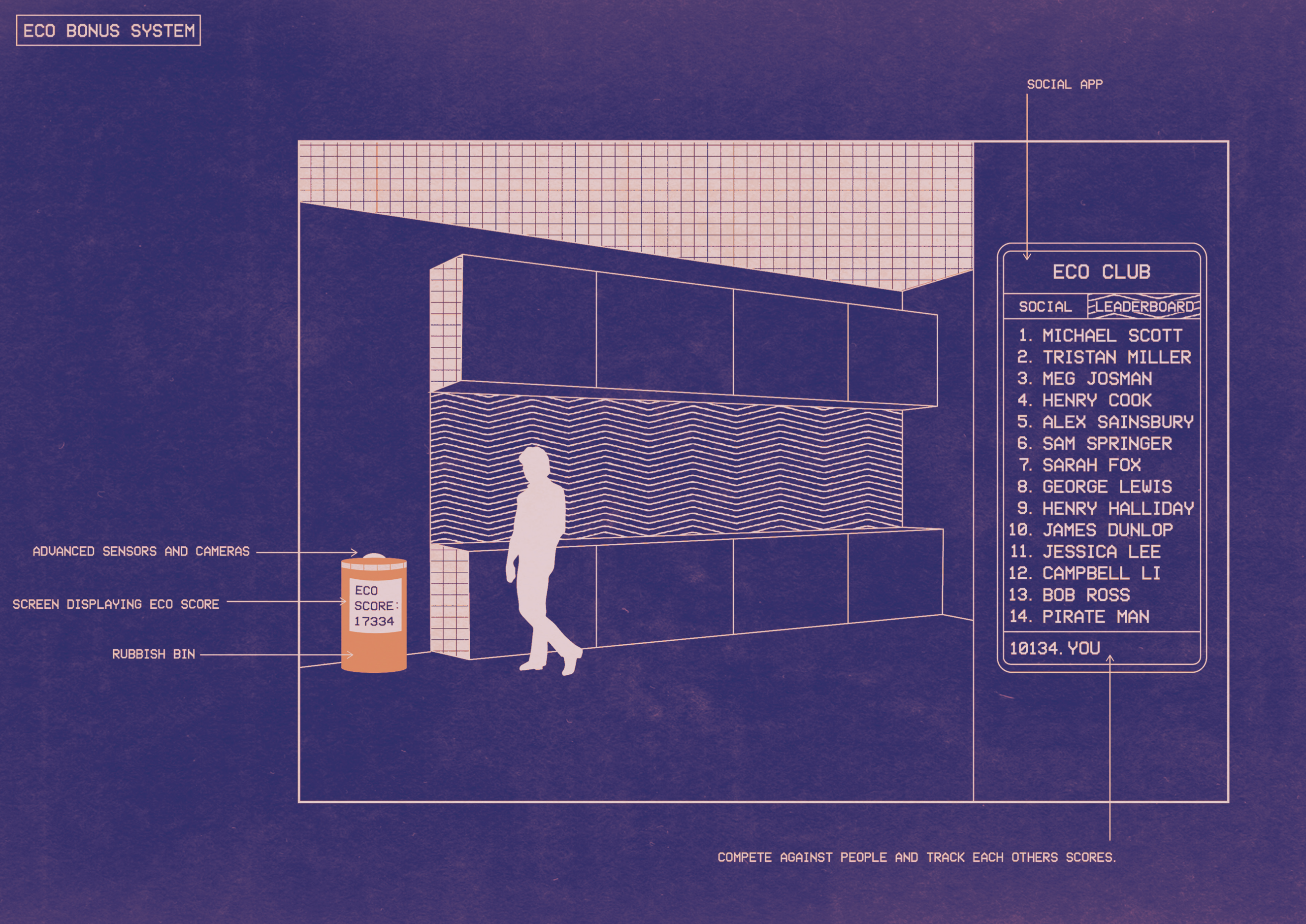

[07] An Eco Social Future