While mood and tone are crucial considerations in evoking the look and feel of alternate worlds, they are notoriously tricky concepts to theorise and teach. Sianne Ngai’s chapter on tone in Ugly Feelings (2009, 38-88) is among the most comprehensive recent efforts to theorise mood and tone. For Ngai, tone and mood are roughly synonymous and encompass both the objective expression of feeling in aesthetic form (the mood of a film or painting, for example) and the subjective element, which is experienced privately (I’m in a bad mood). Mood and tone are irreducible to either purely objective or subjective dimensions in this sense.

A further seeming paradox of tones and moods relates to the difficulty associated with pointing to them as features or attributes of a given work. Ngai cites Susanne Langer’s work Feeling and Form (1953), which encapsulates the simultaneous pervasiveness and intangibility of mood in this regard:

The mood of a landscape appears to us as objectively given with it as one of its attributes, belonging to it just like any other attribute we perceive it to have. . . . We never think of regarding the landscape as a sentient being whose outward aspect “expresses” the mood that it contains subjectively. The landscape does not express the mood, but has it; the mood surrounds, fills, and permeates it, . . . the mood belongs to our total impression of the landscape and can only be distinguished as one of its components by a process of abstraction. (Quoted in Ngai 2009, 45-46)

The drive to analyse in contexts of teaching and research is to some extent inimical to mood defined as a total impression. As educators and researchers we are increasingly obliged to think in mechanistic, analytical modes that take 'the part' or ‘the attribute’ as the defining elements of meaning. How do you build something if not by parts? How can you give feedback if not by specifying which attributes of a work need to be added or removed? And yet, as all teachers and critics know, the total impression of a work cannot necessarily be any better understood by breaking it down into its components.

The same is true when making a work creatively, whether literary, visual, material or spatial. There are certainly off-the-shelf tones that can be constructed based on archetypes—dystopian and utopian futures are common examples in futuring and narrative explorations of technology more broadly—however, moods of greater subtly and originality often emerge through a nebulous, labyrinthine process that involves continual creative experimentation.

Rather than offer prescriptive guidance for the creation of specific moods, design researchers were again offered a number of prompts and examples aimed to avoid the unthinking adoption of a neutral mood, or employing straightforward dystopian or utopian stereotypes. These included the following:

Mood multiplier: often visualisations of future realities need to do subtle and layered persuasive work in order to have the intended impact. For example, particular scenarios might need to effectively communicate the risks or potential failings of a given technology without employing crude and overused dystopian archetypes associated with mastered technology (by humans) becoming the master (of humans). The same goes for the inverse: communicating the potential benefits of a given technology without resorting to techno-messianic or utopian archetypes. Rather than settling on one adjective to encapsulate the tone of the storyworld, aim for three or four that exhibit subtle contrasts.

Image text toggle: If thinking about mood first is a barrier, experiment with different visual styles and toggle between the evolution of a desirable visual style and a description of that style in words. This process should be a staged iteration. Step 1: collect and document inspirational examples and experiment with different approaches to visual design based on these. Step 2: Choose three or four words that encapsulate the style of your prototype images, or ask other people to describe your examples and synthesise your findings. Step 3: Return to the visual design prototypes and refine these based on your emerging design principles/ visual descriptors. Step 4: Repeat Step 2 for further refinement.

Minor moods: Sianne Ngai’s work on minor aesthetic categories (2012) is also a relevant provocation for thinking about tone and mood, whether in a visual, material or narrative sense. Ngai’s minor categories of ‘the cute’, ‘the interesting’ and ‘the zany’ are defined by bipolar affects: tenderness and aggression in the case of the cute, boredom and novelty in the case of the interesting, and stress and fun or play in the case of the zany (Ngai 2012). Thinking about tone and mood as something generated from the tension between contrasting and yet integrated affects is a further means to a more complex and diverse approach to future scenario visualisation.

Continue ︎︎︎

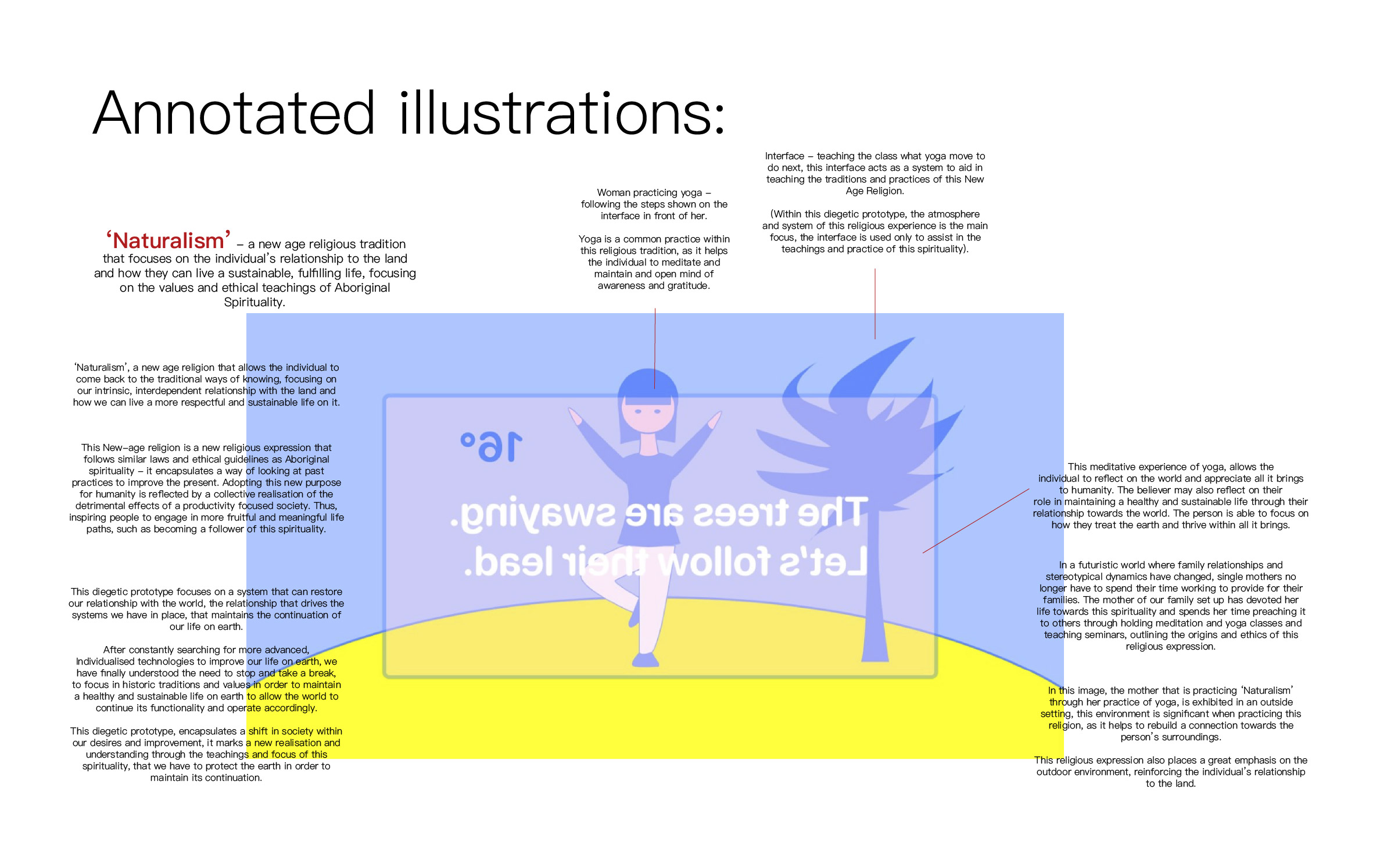

[15] Transforming our Purpose

[16] Sustaining in the Moonlight

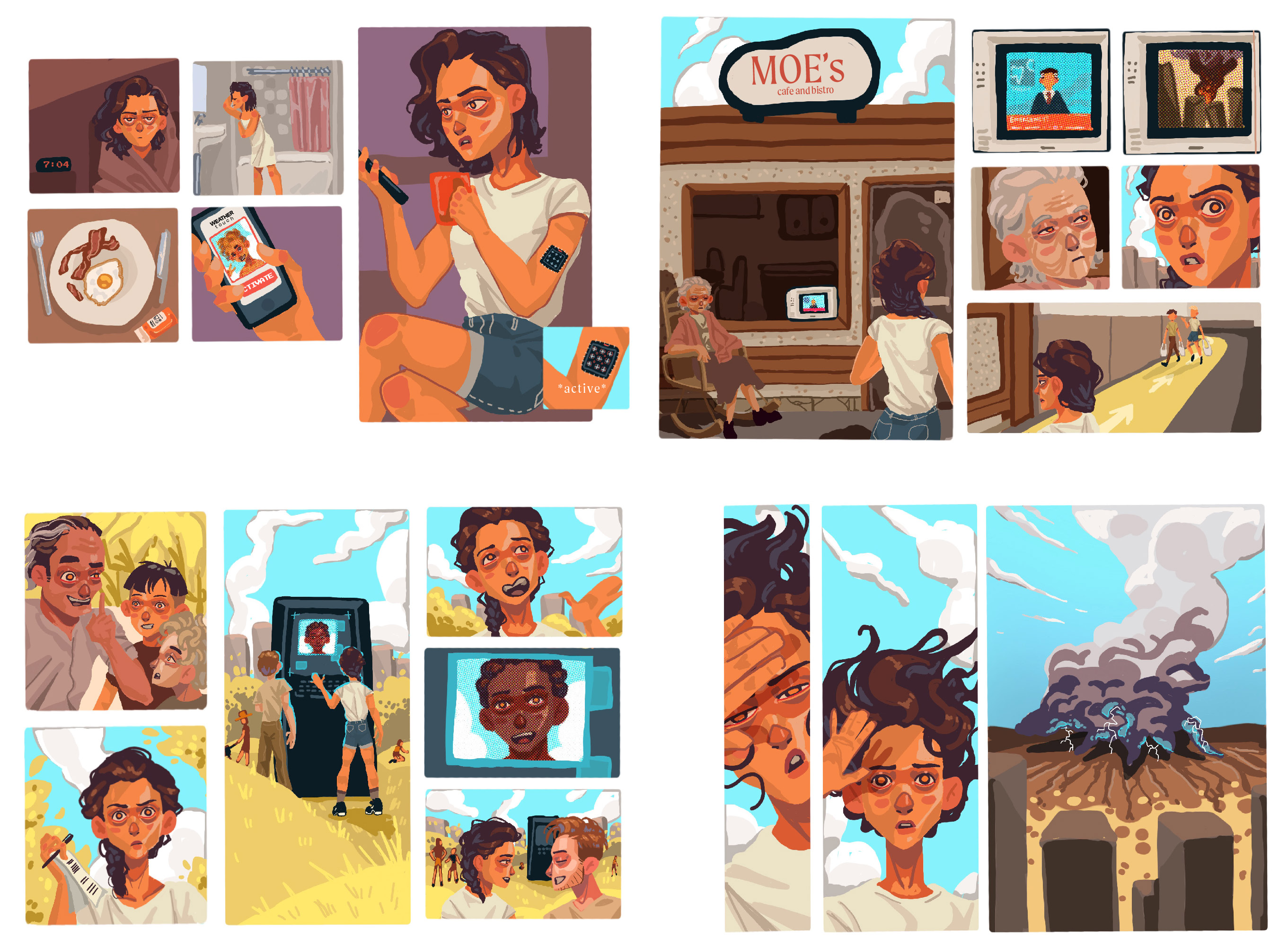

[17] Connection: Or a story of community, the environment, Betty and an oncoming storm

[18] Retail and manufacturing in a Post Climate Change World